- Chris Leadbeater, travel writer

15 JUNE 2017 • 3:35PMFollow

For all the many differences between the cities of the world, the foundation tale of any great metropolis generally runs along the same lines. It may involve settlement on either the bank of a river (London, Paris), or on the edge of the sea (Barcelona, New York, Rio de Janeiro), but the basic spark-point is the same – people finding a reliable, safe and convenient location next to water, and deciding to construct their homes there. Give it a few centuries – and glass skyscrapers and deep-dug Tube systems will eventually follow.

There are, though, occasional exceptions to this theory, and the Ukrainian city of Donetsk is certainly one of them. It does not occupy the flank of a major river (the Kalmius, which passes through it, could scarcely be described as such), nor gaze at an ocean – and it was not founded by Romans, or even ancient Slavic peoples. It is a glitch in the timeframe, forged as recently as the late 19th century – and, in a significant way, in origin, it is British.

It is not, of course, a place which demands tourist exploration. At least, not at the moment. For there Donetsk sits, in the far east of Ukraine, just 60 miles from the Russian border – a conurbation cloaked in smoke, strife and enduring doubts about its status. Indeed, it is difficult to say whether the term “Ukrainian city” is even correct anymore. As of April 2014, it has been part of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” – a self-proclaimed separatist entity, backed by Russia, which is fighting a civil war against its mother nation. This is not a place that anyone should wish to trawl in these dark times.

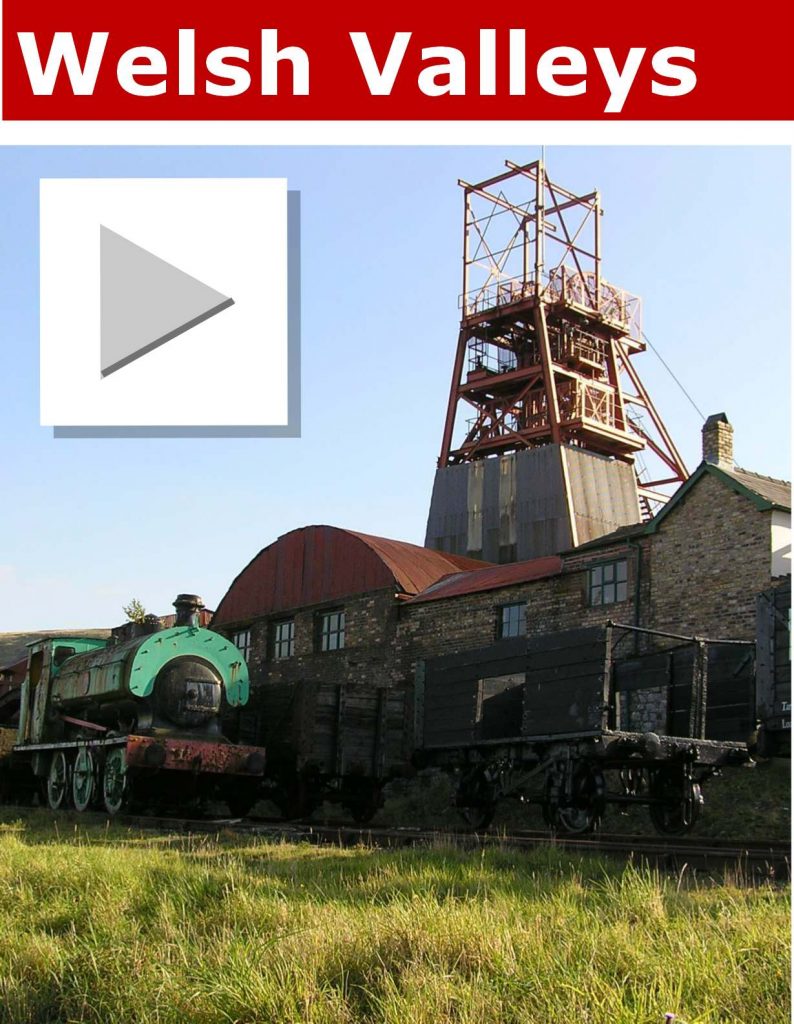

But if Donetsk’s present is tense, its past is remarkable – and it starts not in Ukraine but in south Wales. In Merthyr Tydfil. For it was here, in 1814, that the businessman John Hughes was born – the son of an ironworks engineer whose skill with this key metal of the Industrial Revolution would see him build a city over 2,100 miles from his birthplace.

A man of ambition and aptitude, Hughes followed his father into the world of furnaces and fiery labour – but quickly surpassed him in career achievement. His sharp mind saw him patent a number of inventions in armour plating. By 1842, he had bought a shipyard. By 1850, he owned a foundry in Newport. In the 1850s, he moved to London, to the Millwall Iron Works Company – where he was heavily involved in the cladding of warships for the Royal Navy. And he was a director of the company in 1868 when it received a request from the Russian government – to set up a similar plant inland of the Azov Sea (a sheltered body of water that forms the north-east corner of the Black Sea).

This was to be no small operation. In the summer of 1870, Hughes found himself – and a team of around 100 Welsh miners and metal-workers, sourced from his home turf – sailing east, through the Mediterranean and into the Black Sea. They went in eight ships, with all the equipment and knowledge needed to begin their project from scratch. The “New Russia Company Ltd” settled on a parcel of land close to the River Kalmius (in what is now Ukraine, but was then Russia), which had been acquired from a Russian statesman, and set to work. Within two years, the team had eight blast furnaces up and running. Collieries, mines, brickworks and rail lines followed. So did churches, hospitals, a school and a fire brigade. By the time of Hughes’s death in 1889, aged 75, the site had become a city. And in Russian fashion, it bore the name of its “creator” – Hughesovka.

This tale will be retold at the start of next month, at the wellspring of it all, Merthyr Tydfil.

“Enthusiasm” will be a one-off, one-day exhibition (on Saturday July 1), held at the Old Town Hall, which will cast its gaze back almost 150 years. It will feature letters home, written by some of those itinerant 19th century Welshmen, read by present-day migrant voices in 21st century Wales. This circle will be squared via a display of photos, shot by Ukrainian lensman Alexander Chekmenev, of mining families – the present-day residents of Donetsk – struggling through existence in a city of shell crack and artillery fire. There will also be a screening of Enthusiasm: The Symphony of Donbass – a revealing film, crafted by the celebrated Soviet documentary-maker Dziga Vertov in 1930, which thrust a camera into the sweat, rust and grime of daily life in Donetsk in an epoch when Stalin had ambitious plans for the surrounding Donbass region and its broad mineral resources.

A niche way to spend part of a weekend? Perhaps. But also a worthy one, according to Victoria Donovan – a lecturer in Russian at the University of St Andrews, and co-founder of the Enthusiasm project. “Knowledge of this period in Ukraine and Wales remains very limited, despite its significance to both countries and to our collective understanding of migration and national identity – especially pertinent issues in modern times,” she explains.

But the exhibition will not just be a respectful observance of a sepia yesterday. It will have a critical eye too. “Welsh entrepreneurship contributed to building Donetsk, but it was also a Welsh exploitation of a local workforce that gave rise to popular resentment and political radicalism that fed into the Russian Revolution of 1917,” Donovan adds. “It’s a complex story which challenges our perceptions of Wales and its industrial history today.”

In this talk of dissatisfaction, she alludes to what happened next. Hughesovka may have been a Welsh endeavour at root, but its fabric was soon blown apart by the chill winds of change which gusted across the Russia of the early 20th century. By 1913, the town was producing 73 per cent of the country’s iron ore, but the bursting of the seams that was the Russian Revolution of 1917 changed everything. Hughes had been gone for almost 20 years (he died suddenly on a business trip to St Petersburg) – but his brothers, who were running the metalworks, had to return home as the plant fell under Bolshevik control. As did the majority of the Welsh labourers. In 1924, Hughesovka was re-named “Stalino”, in tribute to a more powerful figure – but it thrived under Communist stewardship. It took on its modern title, Donetsk, in 1961. It is now home to a population of almost a million.

Travellers, obviously, are rather less common in this now-troubled metropolis – which leaves the upcoming exhibition as the best (and the easiest) way to open a window onto a less-read chapter in Britain’s back-story. “The really engaging thing about this project is how much nuance exists in these issues of culture, migration and history which all of us are curently grappling with,” says the artist Stefhan Caddick, the second co-founder of Enthusiasm. “The name of the project comes from Vertov’s title for his Symphony of Donbass . It reflected his and his fellow Bolsheviks’ enthusiasm for the revolution. That his fervour might not have been shared by the Welsh migrants fleeing the revolution makes us consider the human stories bound up in these global events. By looking back at this historic episode, perhaps we can better understand the times we live in today.”

The link between south Wales and eastern Ukraine has not been completely forgotten. In 2014, the Welsh rock act Manic Street Preachers – a band which has often dug into its own national identity for cultural inspiration – included a track called Dreaming A City (Hughesovka) on its critically acclaimed album Futurology. That this four-minute rush of squalling guitars and rumbling bass is an instrumental perhaps says something about the problem of distilling events of the late 19th century into a 21st century pop song. For those wishing for further enlightenment, Merthyr Tydfil will provide it in a fortnight’s time.

Enthusiasm will be held on July 1 at the Old Town Hall, High Street, Merthyr Tydfil (midday-10pm; free admission). Further details atstefhancaddick.co.uk/new/enthusiasm.