The borderland between England and Wales has long been a region of contention. Its distinctive geography, wedged roughly between Welsh mountains and English river beds has not only isolated this rural, sparsely populated slice of land, but created a unique identity. Here we find what Garner (1984) calls “Anglo-Welshness,” in essence a hybridization with Welsh town names and cultural influence on the English side of the border and the opposite in Wales. As Garner states, this quality is “strongest in genuine border towns like Oswestry, Montgomery, Knighton, Kington, Presteigne and Hay-on-Wye, which survived against the odds and are still not quite sure which side they are on. The same feeling is likely to extend to anyone living west of Shrewsbury, Loeminster, Ludlow or Hereford, because towns like these, far more than the political boundary, marked the beginning of England.”

The region is lovely: mountains, moorlands, farms, wooded river valleys, small villages, half-timbered buildings and castles exist side by side. In fact, according to Rowley (1986), the Welsh Marches (as the borders are known) contain the densest concentration of motte-and-bailey castles in Wales and England – not a great surprise, for this was an area of frequent conflict. As early as the Iron Age, disputes occurred on both sides of the borderland. The Romans established forts at Chester, Gloucester and Caerleon along the Marches in an attempt to restrain the rebellious Welsh. And the Anglo-Saxons under the leadership of King Offa of Mercia, built the first barricade along the borders at the end of the 8th century: Offa’s Dyke. (It still divides England and Wales.) Yet, it was only with the arrival of the Normans that the Marches were consolidated into a separate entity.

The term “March” is derived from the Anglo-Saxon “mearc,” which means “boundary.” However, the Marches are much more than a mere boundary between two lands. Although a few Normans had settled in the region prior to the conquest, building castles at such places as Ewyas Harold, Richard’s Castle and Hereford, it was only after 1066 that William the Conqueror sought to formally subdue the borderlands. The Welsh in particular did not gracefully submit to Norman control and resisted for well over 100 years. In order to quell the Welsh uprisings, King William created the Marcher Lordships, granting virtual independence and what amounted to petty kingdoms to over 150 of his most valued supporters. The territories were collectively known as the Welsh Marches (Marchia Wallia), while the native Welsh lands to the west were considered Wales Proper (pura Wallia). Marcher lords ruled their lands as they saw fit, unlike their counterparts in England who were directly accountable to the king. Marcher lords could build castles, administer laws, wage wars, establish towns, and “possessed all of the royal perquisites – salvage, treasure-trove, plunder and royal fish (Rowley)”. People living in the Marches were subject to “the customs of the March,” while those in pura Wallia still adhered to “the laws of Hywel Dda” (indigenous Welsh law).

Major Marcher centers were established at the three largest cities, Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford, and administered by powerful earls. Border castles were also built in: Chepstow, St Briavel’s, Monmouth, Clearwell, Goodrich, Pembridge, Hay-on-Wye, Clyro, Clifford, Clun, White, Skenfrith, Grosmont, Ludlow, Painscastle, Croft, Wigmore, Montgomery, Stokesay, Powis, Hopton, Chirk, Whittington, Longtown, Huntington, and Bridgnorth.

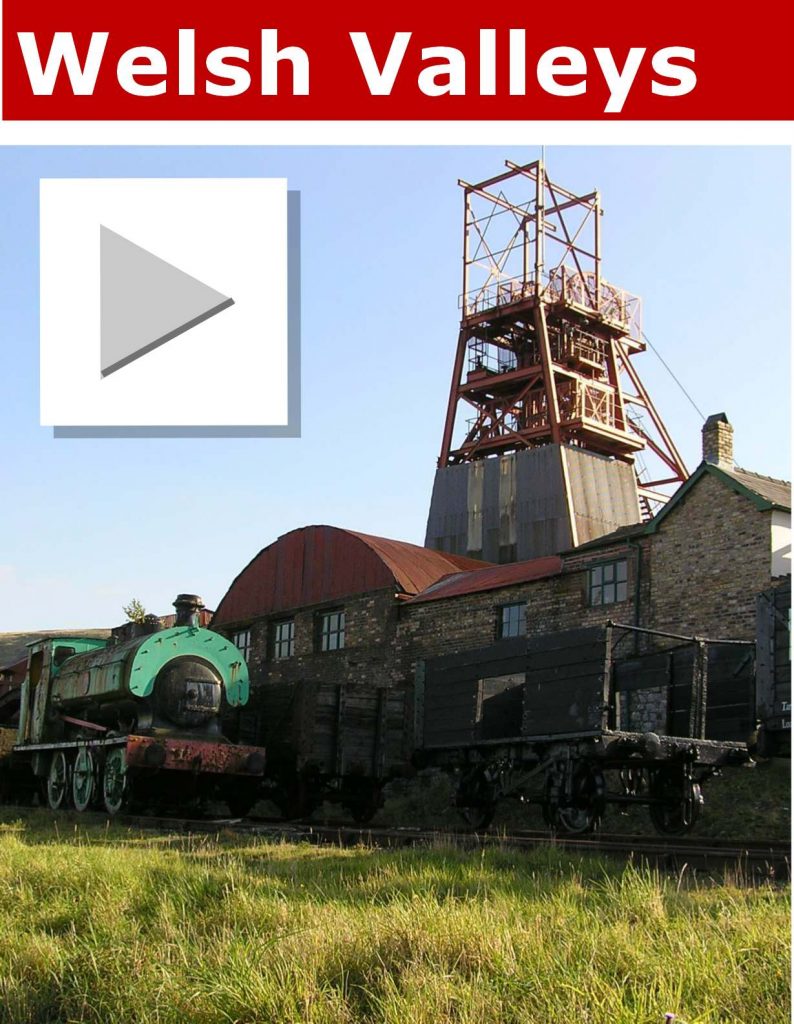

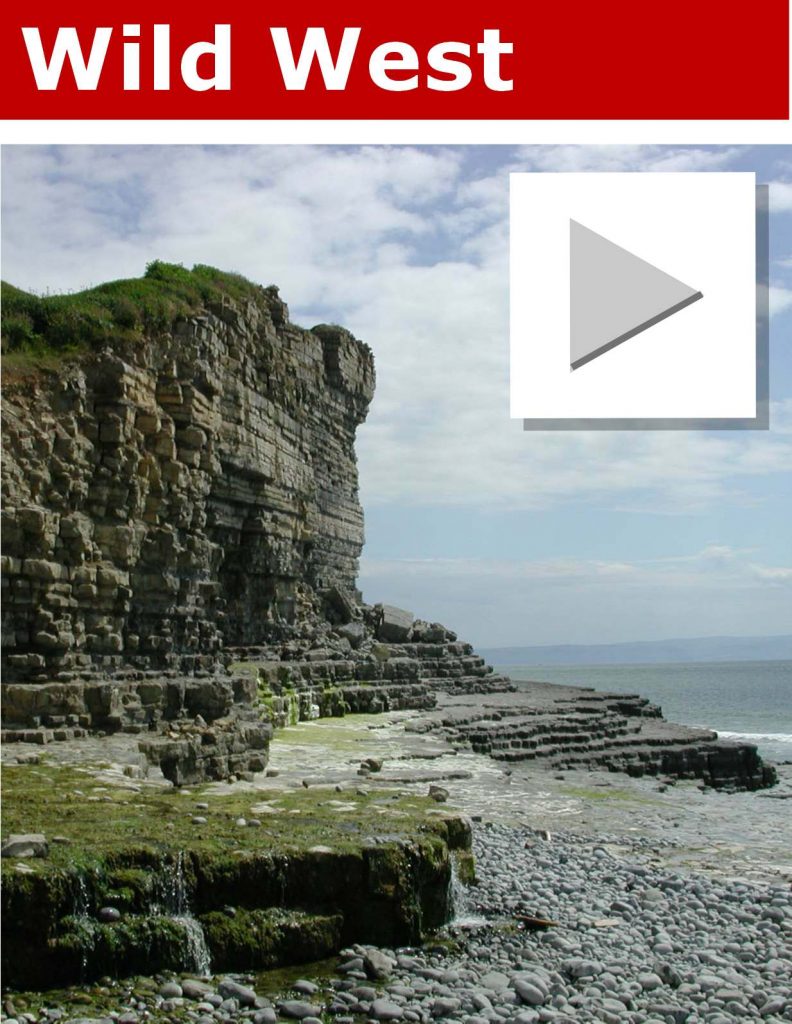

The Welsh Marches offer today’s explorer numerous sites to experience, natural and man-made wonders. While modernization and the Industrial Revolution have altered the economic focus of much of the region, and we now see mining and quarrying in some spots, the borderlands between Wales and England are certainly treasures in their own right, and clearly rival other, more frequented regions of Britain. Most of the above-mentioned castles are open to the public, freely accessible, or visible from the roadside.

Lise Hull owns and operates Castles of Britain, an information and research web site providing a wide range of information on the castles of Britain. Mrs. Hull has a Masters Degree in Historic Preservation, and has visited well over 160 castles in Wales, England, Scotland and Ireland. She welcomes any and all questions concerning the castles of Britain, and invites people to visit her web site or contact her directly via e-mail at: castlesu@aol.com.Copyright © by Richard Williams

The following is an excerpt from “Narberth – Part of a Greater Domain”

For many medieval generations the House of Marshal, headed by the earls of Pembroke, was one of the most powerful families serving the English crown. Indeed, William Marshal, a recipient of the earldom through marriage by the grace of Richard I, was the regent of England during the minority of Henry III, from 1216 until his death in 1219.

Rivalling these achievements, however, was another noble house. The family is more generally associated with the territory in and around the English/Welsh border, The March. However, it did hold sway in part of Pembrokeshire for a long period within its own ascendant years. The house in question was the house of Mortimer, and its part of the county was Narberth.

The Mortimers epitomised the Marcher Lordship. This class of Anglo-Norman nobility had been established by William the Conqueror and perpetuated by his successors, as a means of subduing the Welsh without the active participation of the sovereign and his armies.

In exchange for quelling any uprising on his behalf, the king conferred rights on the Marcher Lords not otherwise granted to the nobility of native England. They were allowed to build castles without royal grant, raise militia and to exact taxes for their own cause. Thus, while acting as a strategic buffer to their king they were also able to command a minor sovereignty within their estates.

As such, they were a powerful factor in the governance of greater England. Indeed, at the time of Edward I there were ten English Earls, of whom seven were Marcher Lords.