Thanks to an intrepid group of Welsh explorers setting sail from their homeland in 1865, a small slice of Argentinean Patagonia will forever be Wales. John Malathronas investigates.

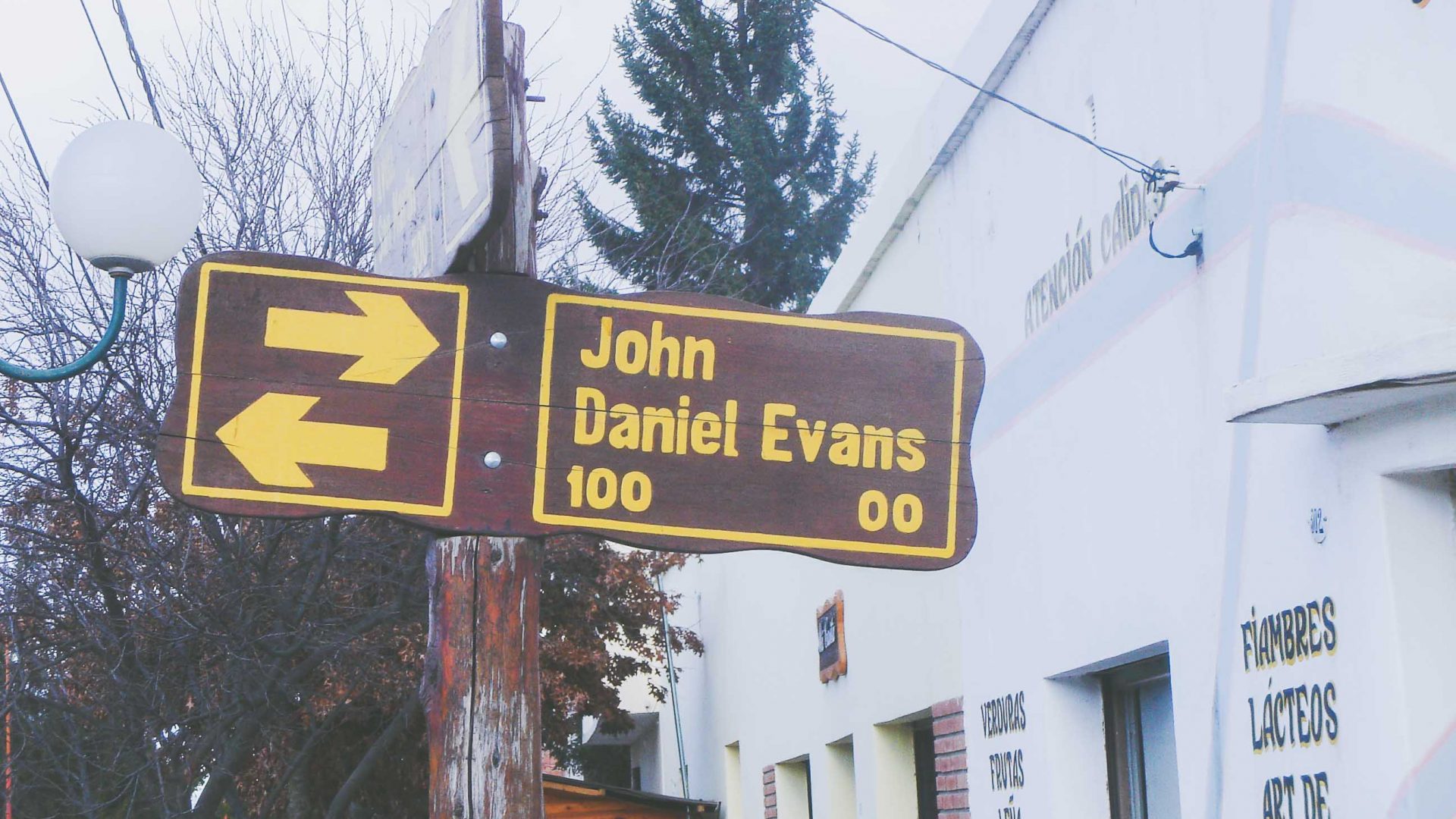

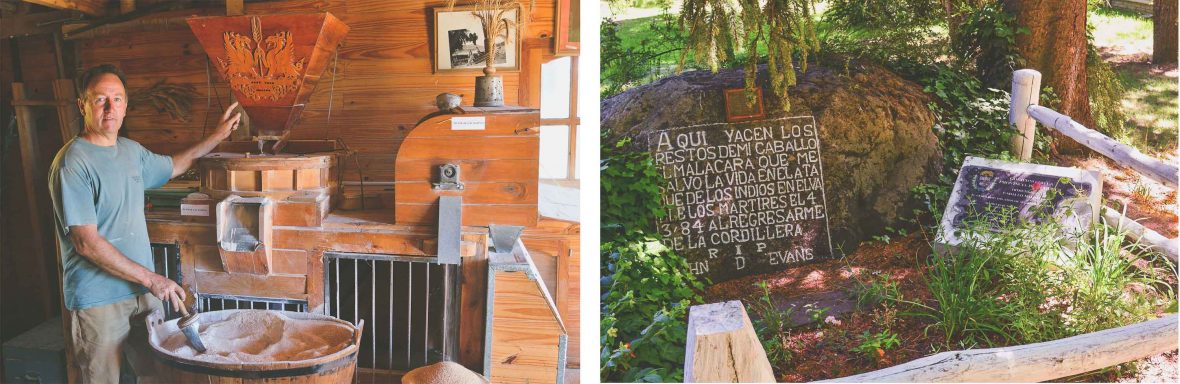

A sign in Spanish hangs on a Monterrey pine: “Malacara, let your memory live with my heirs”. Clery Evans—one of those heirs—points at a corralled grave, the focal point of a large, landscaped garden.

I look down and read: “Here lie the remains of my horse Malacara that saved my life during an Indian attack in the Valley of the Martyrs on 4-3-84 as I was returning from the cordillera.”

Yes, despite the presence of Monterrey pines, I’m not in California. Although I’m surrounded by a well-tended lawn, I’m nowhere near the home shires. I’m in the small town of Trevelin high up in the Argentine Andes and, well, this is the grave of a horse.

Trevelin is a town founded during a wave of Welsh immigration to Patagonia that started with the voyage of the Mimosa in May 1865. Those plucky Welsh pioneers wanted to establish a colony on a vast, almost empty tract of land that was remote enough to escape political control.

RELATED: Is Salta Argentina’s next adventure playground?

The nearest government was headquartered in Buenos Aires, hundreds of miles north, while despised Albion lay on the other side of the world—its small sheep colony of the Falklands opposite having been left to its own devices.

The main settlements were founded in the lower Chubut valley, a short distance inland from the coast: Trelew, Gaiman, Dolavon. Beyond those stretched the arid steppe; it took 20 years for the frequent search parties to discover a fertile valley—Cwm Hyfryd(‘Lovely Vale’)—some 400-odd miles west.

Clery Evans leads me into her bungalow, on whose walls hang fading photos of her grandfather, John Daniel Evans. There she recounts—no, acts—his story to me. How he learned desert survival tricks from the indigenous Patagonian Tehuelche who bartered peacefully with the Welsh. How a later Argentinian policy of rounding up the natives and transporting them to ‘reform towns’ broke that peace. How during one hinterland exploration, Evans and his three comrades were attacked by the Tehuelche. And, finally, how Malacara, his horse, saved him from their lances with a miraculous jump across a 12-foot-long ravine.

Welsh tradition is what travelers come to Trevelin for. They find it in abundance in the two casas de té: Nain Maggie and La Mutisia, where they serve tea and a bounty of cream cakes, baked “after grandmother’s recipes”.

After he reached the coast, Evans returned with an armed unit and found the mutilated corpses of his companions. He had survived a massacre.

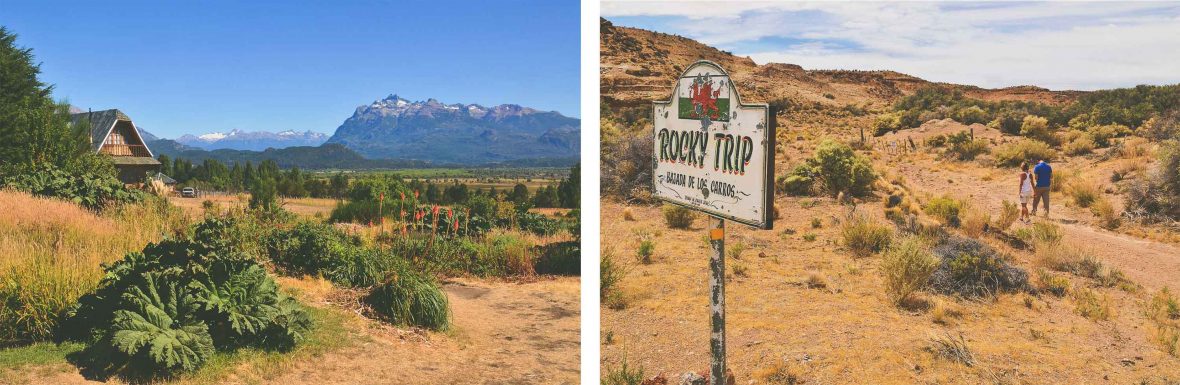

Four years later, John Daniel Evans led a trail of Welsh wagons on an epic trek to Cwm Hyfryd that’s now celebrated in folk memory as the ‘Rocky Trip’. It’s how I ended up here, too: Argentina’s Highway R25 runs along the same route across the Patagonian plain.

Evans was nicknamed El Molinero (‘The Miller’), after the flour mill he founded in Trevelin became a blueprint for the region. At its heyday, there were 22 mills in the area until the 1950s, when the newly-built Patagonian Express brought flour at lower prices from larger enterprises up north.

Today only Nant Fach remains, outside Trevelin, where Mervyn Evans, proud of his Welsh pedigree, single-handedly built a flour mill in his farm “so that the traditional knowledge is not lost”.

Welsh tradition is what travelers come to Trevelin for. They find it in abundance in the two casas de té: Nain Maggie and La Mutisia. With their maps of Wales, red dragon emblems and Welsh language posters, they serve afternoon tea and a bounty of cream cakes, baked “after grandmother’s recipes”.

“We get some tourists, but the majority don’t venture outside Gaiman and Trelew”, says Susanna de la Fuente at Casa Nain Maggie, a corner of the Andes that will forever be Wales. Pictures of Maggie, Susanna’s great-grandmother, adorn the wall along with photos from the annual Patagonian Eisteddfod and postcards from that distant, yet familiar, country they call Cymru. “Visitors from Wales who venture this far are moved to tears hearing their language spoken”, Susanna adds.

The Argentinians have a lot to thank the Trevelin colonists for. When Chile and Argentina divided Patagonia at the turn of the last century, they split the Andes according to its hydrography … this should all belong to Chile.

For decades, Welsh language instruction had been left to retired school teachers who came to Patagonia to keep it alive on their own initiative. Nowadays it’s undergoing a renaissance, funded properly by the new Welsh Assembly. Too late for Oscar ‘Kansas’ Jones, an old cowboy who only speaks Spanish. “Lack of practice”, he says. “The words are in my head but they don’t come out. My paternal grandmother came on the Mimosa, you know. But one of my grandchildren is leaving to study in Wales.”

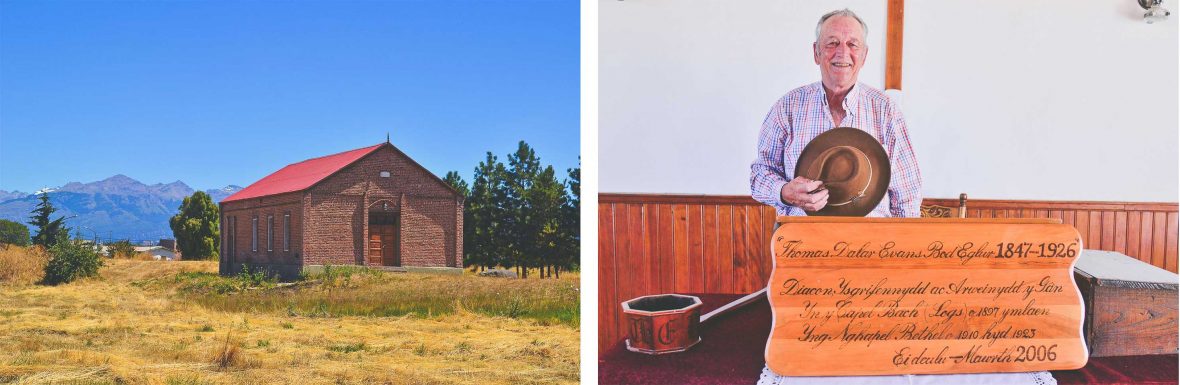

One thing Oscar’s kept, though, is his religion. He unlocks Bethel Chapel that stands on an open field with the Andes spectacularly silhouetted in the horizon. Non-denominational, it was first erected in 1897, but the current brick building with its red corrugated roof and hardwood floorboards dates from 1910.

RELATED: Inside Patagonia’s secret adventure town

“Here I baptized my children in 1970,” Oscar says. We used to have a wandering pastor who came for weddings and baptisms. We now open it for a reunion de canto—to sing hymns every now and again. There are always 60-70 people present.” The pastor’s lodgings today house ‘Ysgol Gymraeg Yr Andes’, a bilingual Spanish/Welsh school funded by the province of Chubut.

The Argentinians have a lot to thank the Trevelin colonists for. When Chile and Argentina divided Patagonia at the turn of the last century, they split the Andes according to its hydrography: The rivers flowing into the Pacific would belong to Chile and those flowing into the Atlantic would belong to Argentina. As Rio Futaleufú drains the region around Trevelin and eventually flows into the Pacific, this should all belong to Chile.

What happened?

On 30 April 1902, there was a local plebiscite under the auspices of Sir Thomas Holdich, a president of the Royal Geographical Society from Northamptonshire. Despite generous Chilean land offers, the inhabitants of Trevelin chose to keep their ties with the coastal Welsh and voted to fly the Argentinian flag.

This, of course, would not have been possible if JD Evans had not led the colonists to Trevelin on the Rocky Trip. And that in turn would not have been possible had Malacara not saved him from the Tehuelche assault. One could venture that it was a horse that gifted Argentina 40,000 square kilometers in the Andes, an area twice the size of Wales.

No wonder his grave is a place of pilgrimage.

This article is from Adventure.com

https://adventure.com/