Brittany – France’s Celtic fringe

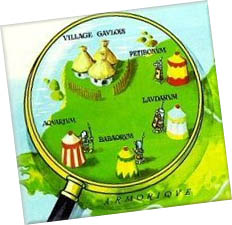

Everyone in France has heard of Asterix – and millions of people beyond France are familiar with Asterix the Gaul, his band of merry men, and their exploits against the Roman invader, as detailed in the classic series of cartoon books that began in the late nineteen fifties, became cult reading in the sixties, and are still going strong.

And as the maps in Asterix books remind the reader, it is in the northwest tip of France that the famous resistance village is to be found. Asterix and his tribe are Gauls, fighting a rearguard action against the “Latin” invaders who had spread across a large part of western Europe, establishing their towns and villas and changing for ever the history of Europe.

As in Britain, where the ancient Celtic tribes were progressively forced back into the western parts of the isles, the Celts of France were also pushed towards the Atlantic by the westward thrust of Romans and Germanic tribes such as the Franks, who eventually gave their name to the land that the Romans had called Gallia – or Gaul – and which we know today as France.

It was only in the furthest northwestern extremity of France that the ancient Gauls, with their Celtic language and culture, managed to survive; and they have done so to this day, leaving Brittany – the land of the Bretons – as the largest outstanding stronghold of Celtic heritage on the continent of Europe.

Brittany shares the folklore of the legendary King Arthur, with the southwest of England During the Dark Ages after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Angles and Saxons invaded Britain, forcing the British who previously inhabited the whole island, to retreat again to their western strongholds; a considerable number of them decided to do so by emigrating south across the sea, to join their cousins in the northwest part of Gaul; and so it was that Armorica, as the area had been know until then, became the land of the Britons, or as we now know it, Brittany. The Bretons are thus the cousins of the Britons, and to this day Brittany and the Celtic parts of the UK share much in common, including a common folklore – involving among others the legends of King Arthur – and similar languages. If you happen to speak Welsh, you may get on well with Britanny’s Breton speakers. Indeed, about 250,000 people in Brittany speak or understand Breton – generally as a second language, and Breton culture and language have undergone a massive revival in the last thirty years, even if they have not acquired the force and status that the Welsh language has regained in Wales.

The Breton identity

Bretons are proud of their identity, and many think of themselves as Bretons before calling themselves French. However, in centralised France, devolution has not occurred to the same extent as in Britain, and while the Breton language is taught in many schools, there is no official Breton parliament, just a regional council that meets in Rennes.

Like their cousins in the islands to the north, the ancient Bretons left to posterity an impressive number of prehistoric sites, most famous of which are the megaliths of Carnac (photo above) in southern Brittany, France’s equivalent of Stonehenge, with its 3000 blocks of granite. But throughout the region, there are dolmens and standing stones whose origins are lost in the mists of time.

Brittany’s cultural identity – officially recognised by a charter signed in 1977 – is expressed through folklore and customs which set it apart from the rest of France. Scots visiting Brittany may be surprised to hear the strains of bagpipes as they wander on holiday through a Breton market; but bagpipes – called biniou or cornemuse, and harps are part of the Breton musical tradition, just as they are in the other Celtic regions of Europe, from western Spain to northern Scotland. Breton music went through a huge revival in the late 1960s and 1970s, with the emergence on the music scene of Celtic rock, led by Alan Stivell, and a group known as Tri Yann, who achieved international fame. Many others have taken up the tradition, and today Celtic rock is a strong sector in contemporary French music.

Throughout Brittany, small festivals and other events strongly stress the region’s distinct Celtic heritage and cultural identity. The most importent event in the annual calendar is however the annual InterCeltique festival, which takes place each year in the first half of August, in the port of Lorient. Started in 1971 on the tide of enthusiasm for the Celtic revival music, the Lorient festival is now one of France’s great summer music festivals, and attracts performers from all over the Celtic regions of Europe, as well as over 600,000 visitors. It includes a Grand parade, with marching bands and musicians from Brittany and other Celtic regions too