Text Copyright © 1995 by Lise Hull

Photographs Copyright © 2002 by Jeffrey L. Thomas.

Above: general view of the castle from the north-west. The great gatehouse of the inner ward (center) is the tallest part of the castle. To the right is the northwest tower, the only round tower at Carreg Cennen.

Below: view of the south curtain wall from the west (left) and view of the gatehouse tower at Carreg Cennen (right)

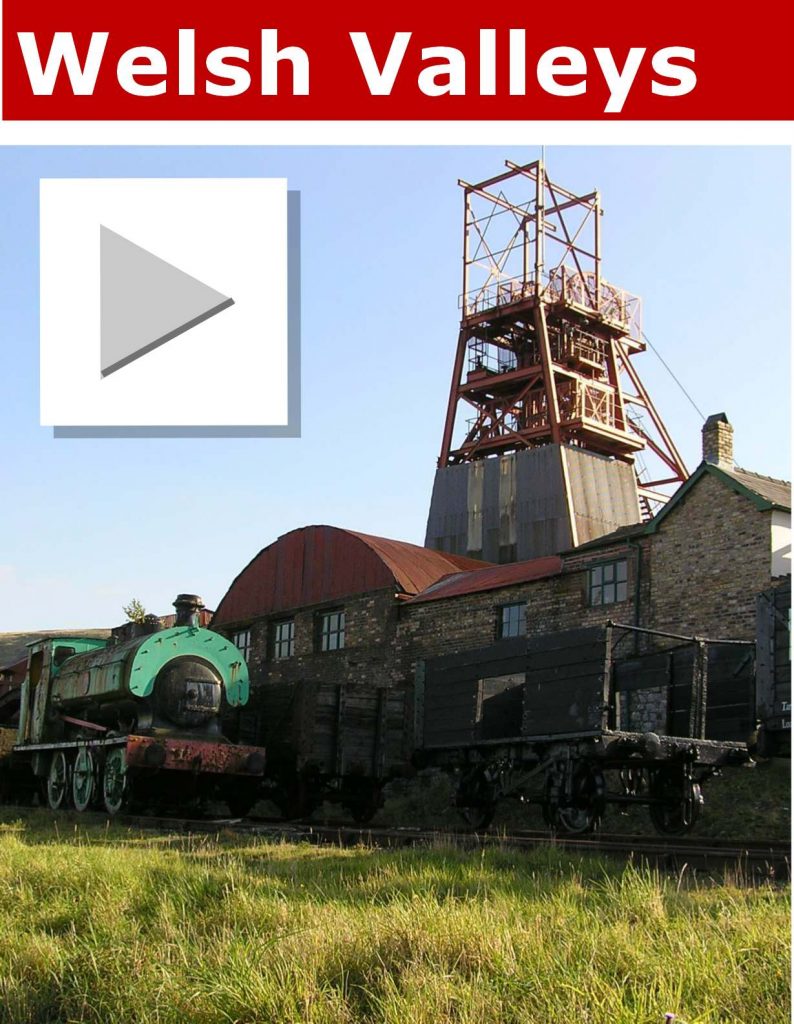

One of the most spectacularly sited Welsh castles is Carreg Cennen, located north of Swansea, a few miles south-east of Llandeilo on a minor road off the A483. Spell-binding views are waiting to be experienced from the sharp hilltop upon which the castle sits. Indeed, Carreg Cennen dominates its surroundings, and seems out of place in the mountainous farming terrain which it commands. The hedgerows along the minor approach road initially obscure views of the site, but suddenly the grey stone fortress springs into your line of sight, enticing you to hurry onwards.

The story of Carreg Cennen Castle is a long one, going back at least to the 13th century. There is archaeological evidence, however, that the Romans and prehistoric peoples occupied the craggy hilltop centuries earlier (a cache of Roman coins and four prehistoric skeletons have been unearthed at the site). Although the Welsh Princes of Deheubarth built the first castle at Carreg Cennen, what remains today dates to King Edward I’s momentous period of castle-building in Wales.Below: Carreg Cennen farm viewed from the summit of the castle.

To reach the hilltop, be prepared for an invigorating climb – and just imagine yourself as an invader intent on the ruin of the castle… The hike will undoubtedly increase your heart beat, at the very least, and make you well aware of your physical conditioning. However, do not be daunted! Little compares to the sense of accomplishment when reaching the top, and you are more than amply rewarded with simply fabulous views of Black Mountain and the colorful, distinctively Welsh countryside.

Carreg Cennen sits on private farm property through which you must pass to gain access to the fortress, which looms well above your head. At first glance this may seem a confusing, unexpectedly contrasting welcome to a castle, with farm animals of many variations roaming all around, but Castell Farm is interesting and adds charm to the day’s events. Looking beyond to the foreboding hillock, you may choose to pause for some refreshment and a look around the farm grounds before venturing forth! Consider a visit to Carreg Cennen as an experience for all your senses – you will not be disappointed!

The excursion upwards finally brings you to the outer ward of the castle, where the view is incredible. Strewn about the ward are rocks and remnants of the outer fortifications. The outer ward enclosed the stables, workshops and lime kilns, and was protected by a small gateway and a stone wall, which continues to your right, around the more vulnerable side of the castle. The enclosure was designed to trap intruders and prevent access to the castle’s interior. The huge North East Tower projected into the ward and was positioned perfectly for an assault on the confined invaders.

The castle’s gatehouse was enterable only after successfully traversing the unusual barbican. Here at Carreg Cennen this defensive outwork consisted of a series of bridges across deep pits, built so that anyone seeking entry was ushered along a narrow walkway complete with sharp, disconcerting turns to both right and left. At any time the bridges overlying the pits could be drawn away from their supports, creating an insurmountable chasm-like barrier. Today the bridges have been replaced by immovable wooden ramps, but the pits remain treacherous and the barbican still intimidates.

While the exterior face of the castle presents an impression of strength and defiance, much of the interior of Carreg Cennen is considerably ruined, the result of demolition in 1462 after the Wars of the Roses. Nevertheless, we can still gain an accurate image of how the medieval fortress would have appeared. What we can see are the remains of several buildings, spaced along the walls of the inner ward. The formidable twin-towered gatehouse on the north wall was the main entry point into the inner courtyard. Immediately before the gatehouse are the remains of the Middle Gate Tower, the last line of defense before the gatehouse was breached. If attackers advanced to this point, they would have been met by a rain of arrows from this tower. (The basement level of the Middle Gate Tower was probably used as a prison.) The gatehouse was also defended with a drawbridge, and contained arrowslits, two portcullises, heavy wooden doors, battlements and machicolations (openings through which water or missiles could be dropped down on fires or unsuspecting attackers). Each octagonal tower also had a ground floor guardroom. Access to the upper floors and the wall- walk was via a spiral staircase, easing movement between the gatehouse and the two northern corner towers. In addition, the gatehouse acted as the castle’s keep, the last refuge during an onslaught.Below: the inner ward at Carreg Cennen showing portions of the gatehouse, hall and domestic buildings.

Just beyond the gatetowers in the inner ward are the remains of baking ovens and two cisterns, which would have caught rain water and augmented the castle’s drinking supply. Curious structures, the cisterns consist of stone-lined pits with low containing walls. The castle’s primary water container was the clay-lined ditch just outside the gatehouse. The wisdom of locating the water supply outside the main castle is questionable, since the water source would have been effectively cutoff in an attack. While the cisterns probably provided adequate short term drinking water, the shallow holding tanks would have been of little use during a protracted siege.

Carreg Cennen’s simple layout provided all the amenities any castle dweller needed. The most built-up side of the fortress is the eastern wing, to the left upon entry, which contained the main domestic chambers. They form a rather compact yet logically laid- out complex of buildings, and would have been the site of most of the castle’s activity. The wing begins with the North East Tower, immediately east of the gatehouse. Possibly used as living quarters for the garrison, the tower contained some basic luxuries of life – a fireplace and latrines – and was located in an excellent strategic position to guard the outer ward, the barbican and the inner ward. Next to the tower was the castle’s kitchen, with its huge fireplace, buttery and pantry. Alongside this structure was the hall, where meals were served and guests entertained. Notably, this room was heated with a central hearth (its base still remains). Beyond the hall is a small tower which projects into the outer ward and held the chapel, a key component of most medieval castles. Lastly, the two rooms of the lord’s private apartments are at the farthest end of the eastern wing. Here a fireplace and decorative windows hint at the status of the occupant.

Below: exterior view of the north west tower and western curtain wall and an ornate window from the King’s Chamber

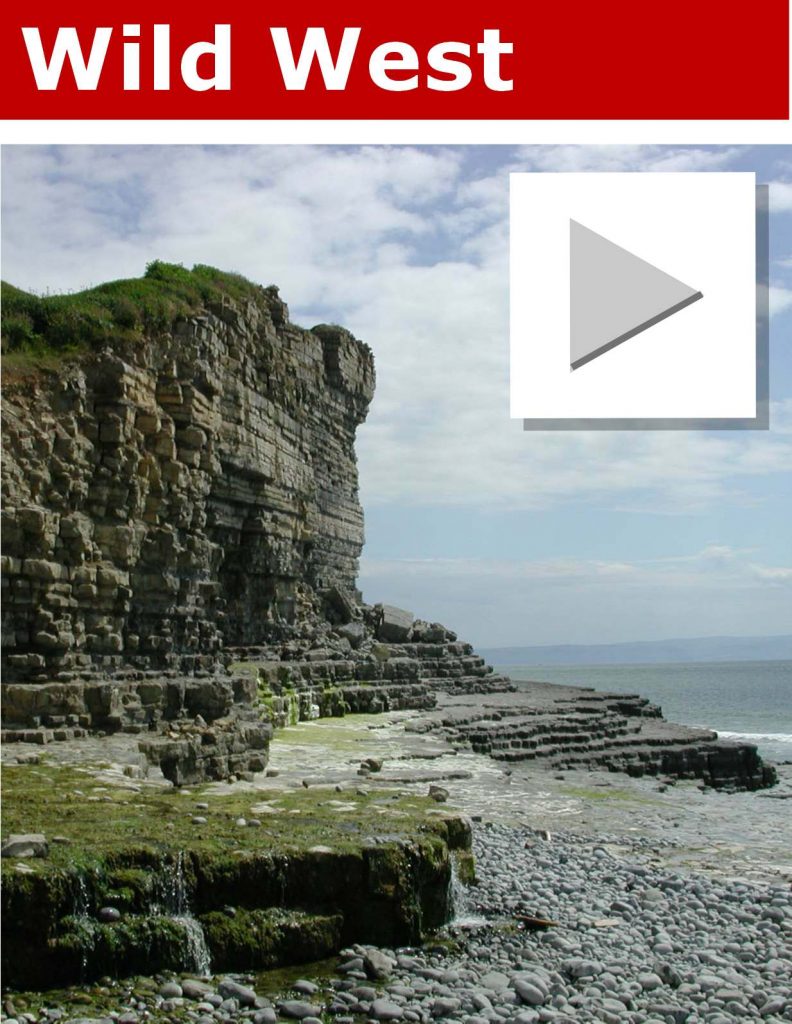

Little remains along the south and west walls of the inner ward. The plain south curtain, with portions of the wall-walk still intact, rises to its original height. The precipitous drop outside made more elaborate defenses unnecessary. The wall held latrines and two windows with stunning views. Foundations of a rectangular structure are visible along the south wall, but the building’s purpose is unclear. The intersecting arrowslitted west wall was built directly on the limestone bedrock and is poorly preserved. It is bounded by the simply-constructed South West Tower and the interesting North West Tower.

The North West Tower guarded the most vulnerable side of the fortress, and its round design would have afforded an all- encompassing view of approaching visitors. The basement had three arrowslits, one of which was altered in the 15th century to accommodate a new advance in weaponry: the musket. Why this tower was the only one with a gunport is uncertain, but the gun’s longer range would have greatly enhanced its defensive impact.

The most exciting feature at Carreg Cennen Castle awaits exploration at the south east corner of the inner ward. Here a steep set of steps leads down past a postern gate into the bowels of the castle, and beyond into a damp limestone cave. Your footing may become unsure as you travel deeper inside, and torches are a necessary aid, for the exterior world rapidly falls away into complete darkness. The bedrock is cut by several of these natural fissures, but only one was modified for use inside the castle. Much of the passageway was carefully lined with stone and the ceiling vaulted. A series of pigeon holes was built into the wall, forming a dovecote (to breed a winter food supply, or possibly to house homing pigeons).

Below: the entrance to the cave from near the King’s Chamber (top left), the vaulted passage leading to the cave (top right), and the actual cave (bottom left & right).

Several theories have been offered to explain the revetting of the fissure. One explanation for altering the passage relates to the water collected in the cave. It has been speculated that this supply would have provided ample drinking water for the castle, especially in times of siege, and that reinforcing the passage would have allowed safe access to the water source. However, since the spot retains only a small amount of moisture, the supply would have been undependable. Originally, the mouth of the cave was open to the outside, making the castle vulnerable to infiltration by the enemy. However, the exterior end of the fissure was intentionally blocked from the inside and effectively impeded outside access. Nevertheless, this flaw in the bedrock would have provided opportunity for undermining by the enemy, who could have gained access to the inner ward or bring down the outer wall of the castle with relative ease. Lining the passage with stone would have buttressed the breach in the bedrock and made the area less susceptible to collapse. Consequently, enemy mining would have been less successful and heavy structures could be built over the reinforced passageway without fear of failure. Carreg Cennen is one of the few castles in Britain to possess such an intriguing natural phenomenon.Below: general view of the castle from the west.

Carreg Cennen Castle had a long and eventful history, having changed ownership numerous times. Legendary references place the original fortress in the Dark Ages, held by Urien Rheged, Lord of Iskennen, and his son Owain, knights during the reign of King Arthur. Stories claim that there is a warrior (perhaps one of the knights, or Arthur himself?) asleep beneath the castle, awaiting a call from the Welsh. The first castle on the site was probably built by the Welsh Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, in the late 12th century. His descendant, Rhys Fychan, eventually inherited the castle, but was betrayed by his mother (the Norman Matilda de Braeos) who turned over the stronghold to the English. Rhys Fychan regained control of the castle in 1248, but had it taken away by his uncle, Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, and then seized in 1277 by King Edward I. From that time onwards, the fortress remained in the hands of the English.Below: view of the south curtain wall from the east perched over its imposing cliff.

The original Welsh stronghold was demolished in the late 13th century and replaced with the imposing structures we see today, by John Giffard and his son. Other owners included Hugh le Despenser, John of Gaunt and Henry of Bolingbroke (the future King Henry IV). Upon Henry’s accession, the castle became Crown property. It was besieged during the rebellion of Owain Glyndwr in about 1403 and was considerably damaged. During the Wars of the Roses, Carreg Cennen’s owners unfortunately sided with the Lancastrians. After the Yorkist victory in 1461, the castle was deemed too much of a threat to the monarchy and was destroyed the following spring.

Despite its ruinous state, the castle was considered a prize. Later owners included Sir Rhys ap Thomas and the Vaughans from Golden Grove, who left the castle to the Earls of Cawdor in the early 19th century. Although Carreg Cennen was placed under the guardianship of the Office of Works in 1932, the Cawdors continued to hold the castle well into the 20th century. Apparently, in the 1960’s Carreg Cennen Castle was acquired by the Morris family of Castell Farm, when Lord Cawdor inadvertently made a mistake in the wording of the deeds and included the castle as part of the farm. Today, the castle is maintained by CADW: Welsh Historic Monuments, the agency which does an outstanding job preserving the architectural heritage of Wales.

Lise Hull owns and operates Castles of Britain, an information and research web site providing a wide range of information on the castles of Britain. Mrs. Hull has a Masters Degree in Historic Preservation, and has visited well over 160 castles in Wales, England, Scotland and Ireland. She welcomes any and all questions concerning the castles of Britain, and invites people to visit her web site or contact her directly via e-mail at: castlesu@aol.com.