Below: Tomb effigy of William Marshal at Temple Church, London.

In a room of the Tower of London in August 1189, two people who were about to be married met for the first time. This twist of fate or act of destiny would have a far-reaching effect on English history. The young lady was Isabel de Clare, sole heiress of Richard Strongbow de Clare, Earl of Pembroke and Striguil, and Aoife, daughter of Dermot MacMurrough, King of Leinster. The man was William Marshal, the second son of John the Marshal and Sibyl, sister of Patrick, Earl of Salisbury. There are no accounts of this first meeting nor of their marriage ceremony, but this was the final step in the making of one of the greatest knights and magnates of medieval English history.

William Marshal’s life is well documented because less than a year after his death in 1219, his eldest son William II commissioned a record of his father’s life. “L’ Historie de Guillaume le Marechal,” is a metrical history of a man and of the knightly class in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century. Little is known about the writer of “L’ Historie” except that his first name was Jean, that he personally witnessed some of the events in Marshal’s later life, and that he had access to Marshal’s squire John D’Erley. The point of view is that of the secular knightly class and not of the ecclesiastical class. The events recorded in “L’ Historie” can be verified in most instances by the official records in the Pipe Rolls, Charter Rolls, Close Rolls, Patent Rolls, Oblatis Rolls, and chronicles of the times.

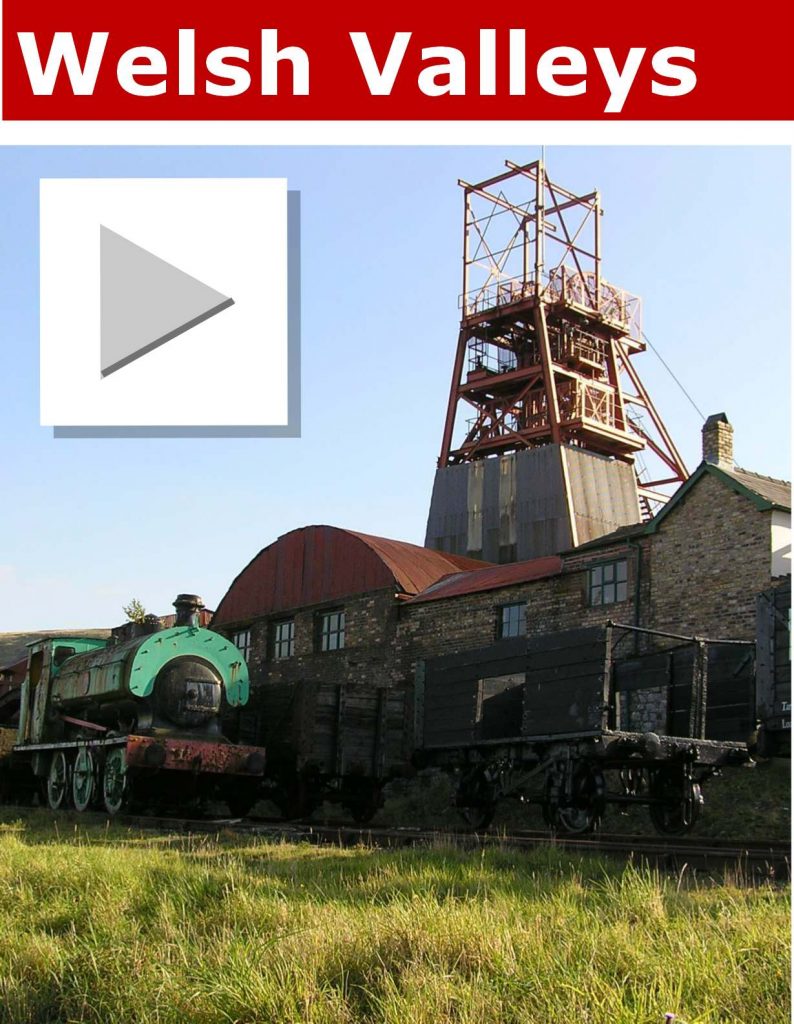

William Marshal was born c 1146, and as a younger son, becoming a knight was his natural choice of a path to success and survival. Marshal was sent to his father’s cousin William of Tancarville, hereditary Chamberlain of Normandy, to be trained as a knight in c1159. He was knighted, probably by his uncle, in 1167.Below right: William Marshal’s Great Tower at Pembroke Castle.

In 1170 William Marshal was appointed head of the mesnie (military) household of the young Prince Henry by King Henry II. From this time until young Henry’s death in June of 1183, Marshal was responsible for protecting, training and running the military household of the heir. In 1173, William Marshal knighted the young Henry, and thereby became Henry’s lord in chivalry. We know that Marshal led young Henry and his mesnie to many victories on the tournament fields of Normandy. It is during the years from 1170 to 1183 that William Marshal established his status as an undefeated knight in tournaments. It is here that Marshal began to establish his friendships with the powerful and influential men of his day. His reputation and his character were built through his own actions and abilities. In this age of feudalism, Marshal was a landless knight. He had no lord from whom he could gain advantages or status.

On the death of the young Henry, Marshal obtained permission from Henry II to take the young Henry’s cross to Jerusalem. Marshal spent two years in the Holy Land fighting for King Guy of Jerusalem and the Knights’ Templar. There are no known records of his time in the east, but we know that some of the castle building techniques he later used at Pembroke were probably learned here.

Henry II granted Marshal his first fief, Cartmel in Lancashire, in 1187. With this fief Marshal became a vassal of King Henry II and swore fealty to him as his lord and his king. Until Henry II’s death in 1188, William Marshal served as his knight, his counselor, and his ambassador. When Richard I came to the throne, he recognized Marshal as a brother and equal in chivalry. Fulfilling the promise made by his father, Richard gave Marshal the heiress Isabel de Clare and all her lands in marriage.

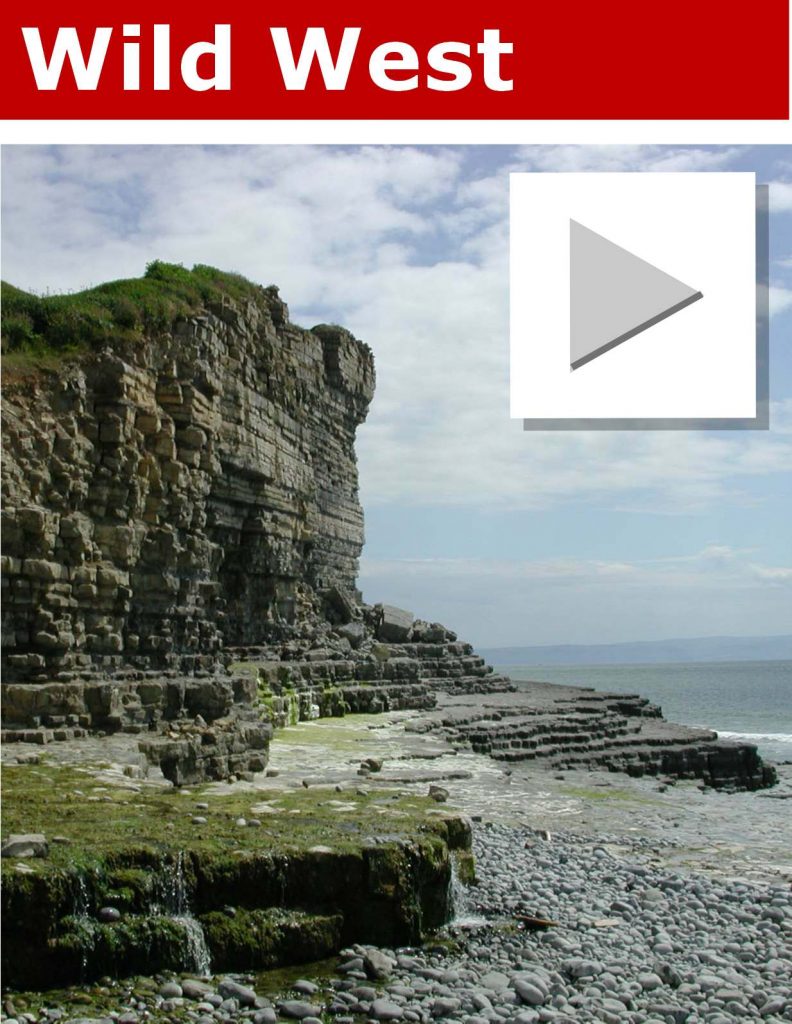

With this marriage, William Marshal became “in right of his wife” one of the greatest lords and magnates in the Plantagenet kingdom. Isabel brought to Marshal the palatine lordships of Pembroke and Striguil in Wales and the lordship of Leinster in Ireland. These were large fiefs of land where the lord held as tenant-in-chief of the Crown. A palatine lord’s word was law within his lands. He had the right to appoint his own officials, courts and sheriffs, and collect and keep the proceeds of his courts and governments. Except for ecclesiastical cases, the king’s writ did not run in the palatinates. King Richard also allowed Marshal to have 1/2 of the barony of Giffard for 2000 marks. This barony was split with Richard de Clare, Earl of Clare and Hertford, who held the barony in England as lord while Marshal held the land in Normandy as lord. This gave Marshal the demesne manors of Crendon in Buckinghamshire and Caversham in Oxfordshire, for 43 knights’ fees, and the fief of Longueville in Normandy with the castles of Longueville and Mueller and Moulineaux, for about 40 knights’ fees.Below: Chepstow Castle in south Wales.

Marshal considered the lands that he held to be one unit, not separate units of English, Irish, Welsh, and Norman lands. They were a compact whole to be preserved and improved for the inheritance of his children. Marshal used what he had learned fighting in Normandy and in the Holy Land to improve these fiefs. The great Tower, the Horseshoe Gatehouse, and the fighting gallery in the outer curtain wall at Pembroke were built under his guidance. At Chepstow (Striguil), he was responsible for the gate in the middle bailey, the rebuilding of the upper level of the keep, the west barbican, and the upper and lower bailey. Marshal was also responsible for the building of the castle at Kilkenny, the new castle at Emlyn, and for taking and improving Cilgerran. From a list of castles by R. A. Brown for the period from 1153 to 1214, Marshal held Chepstow, Cilgerran, Emlyn, Goodrich, Haverford, Inkberrow, Pembroke, Tenby, and Usk in England and Wales. Just these castles would have produced more than two hundred knights’ fees owed by Marshal to the Crown. Without including his lands in Normandy and Ireland, as feudal lord Marshal controlled a vast amount of land, wealth, and knights/vassals in the Angevin kingdom.

William Marshal served King Richard faithfully as knight, vassal, ambassador, itinerant justice, associate justiciar, counselor, and friend. On Richard I’s untimely death in 1199, William Marshal supported John as heir to the throne rather than John’s nephew, Arthur of Brittany. It was King John who belted William Marshal and created him Earl of Pembroke on the same day that John was crowned King, May 27, 1199. It is during King John’s reign that the character of William Marshal is clearly revealed. John’s character has been drawn by countless historians, and none have been able to erase the ineptitude that King John displayed when dealing with his English barons. Whatever his motives were, John inevitably alienated his greatest barons despite the fact that he needed their support and loyalty to rule England. William Marshal was a powerful, respected, wise and loyal knight and baron who had already served two Angevin kings. King John, however, accused Marshal of being a traitor, took all of Marshal’s English and Welsh castles, took Marshal’s two older sons as hostages, tried to take Marshal’s lands in Leinster, and even tried to get his own household knights to challenge Marshal to trial by combat. Despite all of this, William Marshal remained loyal to his feudal lord. He did not rebel when John took his castles; he gave up his two sons as hostages; he supported John against the Papal Interdict; and he supported John in the baronial rebellion. Of all the bonds of feudalism, the greatest and the most important bond was the one of fealty, of loyalty to one’s lord. To break this bond and oath was treason, and this was the greatest of crimes. William Marshal was the epitome of knighthood and chivalry. He did not simply espouse it. Marshal’s entire life was governed by his oaths of fealty and by his own innate sense of honour. If Marshal had taken his lands, castles, and knights to the side of the rebellion, King John would have lost his crown and perhaps his life.

On the death of John, October 19,1216, William Marshal was chosen by his peers in England as regent for the nine year old Henry III. Henry was knighted and then crowned under the seal of the Earl of Pembroke. William Marshal was the main force and impetus for the defeat of Philip II of France, even leading the attack to relieve Lincoln castle in May 1217 though he was seventy years old. On September 11, 1217, Marshal negotiated the Treaty of Lambeth that ended the war. By his wise treatment of those English barons who had supported Philip II against King John, Marshal ensured the restoration of peace and order in England. This undefeated knight had become a great statesman in the last years of his life. William Marshal died May 14, 1219 at Caversham and was buried as a Knight Templar in the Temple Church in London.Below: Temple Church, London, where William Marshal and two of his sons are buried.

William Marshal had been born during the Civil Wars of King Stephen and Empress Mathilda. He trained and knighted one intended king; served faithfully Kings Henry II, Richard the Lionheart, and John Lackland; and knighted and served as regent for a fourth king. As “rector regis et regni,” Marshal had the Great Charter reissued in 1216 and in 1217 for the welfare and future of England and the Crown. There are many explanations and definitions of Marshal, his life and his time. Some say he survived so long and so well because of his physical stamina and condition, that he was simply a man of great physical strength. This gives only a piece of the complete portrait of William Marshal. He was a brilliant strategist in terms of his world, militarily and politically. He lived and survived in Henry II’s arena, earning Henry’s respect and affection. No man of little intelligence would have survived very long there. William Marshal can be understood in terms of his world of feudalism, fealty, loyalty and honour. Marshal stood by King John because of Marshal’s oath of fealty and homage to his “lord,” who also happened to be the King. William Marshal was a man who lived his life according to his sense of honour, and his sense of honour was defined in the laws and customs of feudalism and knighthood. It is that sense of honour that made no man equal to William Marshal, knight, Earl of Pembroke and Striguil, Lord of Leinster, and Regent of England.